History rarely offers second chances. But in the early 1990s, as Poland emerged from the wreckage of communism, it found itself at the epicentre of an unprecedented free market revolution. The helm of polish finance ministry were taken over by prof. Leszek Balcerowicz. The lonely liberal who had lurked in the cracks of communist academia and his small fellowship of allies sketched out a plan for a feat that had never been attempted before: to transform a command economy into a free market one. He had 600% inflation, an economy with 90% state-owned industries, and a banking system ready to implode staring him down.

But he pulled it off. Inflation was crushed, industries were privatized, and the country somehow avoided total collapse. Poland became a free market economy in a shockingly brief period.

Out of this chaotic transition, which some would later label “the era of savage capitalism,” came some of Poland’s most successful and globally recognized companies. One such case started with just two guys selling pirated copies of video games in an underground bazar. Over time, the company cleaned up its act, evolving from a shady distributor to a game developer, eventually conquering the gaming world with The Witcher III: Wild Hunt and Cyberpunk 2077 productions.

The era of wild capitalism did not last. Over time, the state gradually reclaimed its former grip. Healthcare was re-centralized into a dysfunctional, state-run insurance monopoly. Taxes soared mercilessly, while meagre pension funds were ransacked and squandered on welfare programs to secure electoral victories. Once-privatized banks fell back into government hands, and the economy suffocated under the weight of relentless regulation. This is the Poland from which the two figures in question emerged. A land of rapid change and growth but also consistent setbacks of government intervention.

Businessman No.1

The first man was born in the city of Toruń. A teacher’s child, he quickly excelled in school, balancing books with part-time work as a football hooligan. He earned a degree in physics, only to abandon science in favour of a master’s in economics. After writing a thesis on public debt, he quit that path as well, turning instead to business.

He began with a small currency exchange—an industry that, at the time, was deeply entangled with the mafia. After turbulent three years, he walked away, leaving with enough seed money for his next venture: a hunting shop. But this, too, was just a stepping stone to his most important enterprise—tax consultancy.

In a country ridden with an elaborate and constantly shapeshifting tax code, Sławomir Mentzen slowly grew his firm, from a one-man operation into a thriving corporation. His clients were mostly limited to a few little-size firms, but within a few years, he found the perfect marketing tool for his services: politics.

Ever since his university years, Mentzen had been a devotee of Poland’s prime political pest: Janusz Korwin-Mikke. The eccentric bowtie-clad ideologue was a peculiar mix of Nigel Farage and Vermin Supreme—part firebrand, part caricature. For decades, Korwin stood as a lone voice for quasi-libertarian ideals. Under communism, he railed against socialism in the clandestine press, defying the regime so openly that he ended up in prison. But when the Iron Curtain fell, he emerged championing free markets and leading his political party into Poland’s first democratic parliament. He shook hands with Milton Friedman, exchanged words with Margaret Thatcher—briefly standing among the giants of his ideology.

But that was where his admirable political journey ended.

Defeat after defeat pushed him into an insular, reactionary niche, where his brand of paleo-politics poisoned the discourse of liberty and free markets for years to come. More than a decade in the political wilderness followed, his influence dwindling to single-digit election results.

Then, unexpectedly, the internet resurrected him.

Korwin became a digital phenomenon, capturing the imagination of Poland’s youngest voters in a way no other politician had. His blog soared to become the most popular in the country, drawing a fervent, cult following. And with this newfound internet fame came an improbable political comeback— he gained a seat in the European Parliament.

It was around this time that Mentzen finally stepped out of the backseat and joined the party he had long cheered from the sidelines. At first, he was shy and nerdy, more comfortable with numbers than with crowds. But slowly, he rose through the ranks, honing his public speaking skills and carving out his place in a party held back by a policy platform built on street-smart conservatism and the divine revelations of Korwin-Mikke.

Mentzen brought what the movement desperately lacked: economic expertise. And as his profile grew, so did his opportunities. Invitations to podcasts and media appearances started rolling in. A politics-business pipeline was built. He would go on air to discuss economics and taxation and advertise his tax consultancy to an entrepreneurial audience. After all, who better to handle your taxes than a man who believes taxation is theft?

Mentzen was hungry for power, but clever enough to wait.

He stood by his leader through every embarrassment, every scandal. He did not flinch when Korwin raised a Roman salute in the European Parliament. He did not object when his mentor’s sexist tirades landed Korwin across from Piers Morgan on Britain’s biggest morning show. He nodded along when Korwin proposed aligning Poland with Russia and hatemongered against immigrants.

He did not criticize. He endured through all the eccentricities of his master. He waited for the right moment to come.

Businessman No.2

The second man came from a small village in the Silesia region of Poland. He was just twelve years old when he watched communism crumble, an era-defining moment that would shape his understanding of opportunity and resilience. As Poland transitioned into a free-market economy, so too did young Rafał Brzoska’s ambitions begin to take shape.

He moved to Cracow to study economics, but his true education took place outside the lecture halls. In the cramped quarters of a student house, he conceived a simple yet effective business: flyer distribution. Through sheer grit and persistence, he turned a modest investment into an empire. Within seven years, his workforce swelled to over 7,000 people across Poland, distributing a staggering 1.2 billion flyers annually through 40 branches.

By 2006, he had amassed the resources to challenge one of Poland’s most entrenched monopolies: Polish Post. For decades, the state-run behemoth had held an iron grip over mail delivery, growing notorious for lost letters, endless queues, and agonizing delays. Bills and legal documents vanished into bureaucratic limbo, and customers endured hours in overcrowded post offices, waiting to send out mail that often never arrived.

Up until that point Polish Post was the government enforced sole distributor of all letters below 50 grams, and official documents. While the EU had been putting on pressure to liberalize the market and privatize the company for the last 19 years, to this day [March of 2025] it remains bankrolled by the taxpayer. Polish Post was at the time one of the most hated institutions in the country. Unreliability, inefficiency, and endless queues at its offices was its trademark.

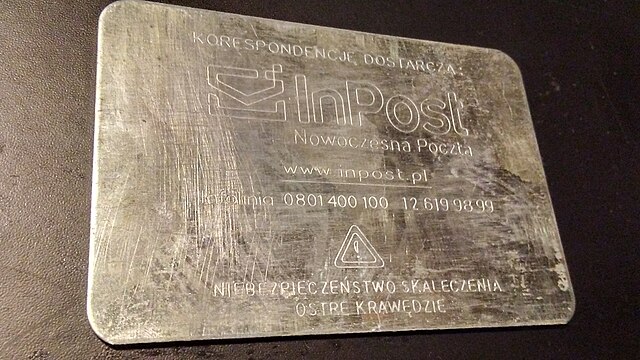

Brzoska, however, had a plan. His new company, InPost, had the manpower and logistical network to compete with the bloated giant, but the law forbade private firms from delivering standard letters under 50 grams—effectively barring him from the bulk of the market. So he found a loophole. To every letter sent a steel weight plate would be attached, artificially increasing their mass above the legal threshold. With this simple trick, a letter became a package, sidestepping the restriction entirely.

Weight plate for letters InPost in Poland

His move couldn’t have been more perfectly timed. InPost launched its assault on Polish Post during a nationwide postal workers’ strike, seizing the opportunity to prove itself as the faster, cheaper, and more reliable alternative. At its peak, InPost captured 16% of the letter delivery market—an unprecedented achievement in a sector where state dominance had seemed unshakable.

In 2009, Brzoska pivoted towards e-commerce deliveries, recognizing the untapped potential of automated parcel lockers. While the concept was virtually unknown in Eastern Europe at the time, he spearheaded its adoption, revolutionizing last-mile delivery and expanding across the region.

But the state wasn’t willing to concede defeat. In 2015, just as InPost was in the midst of preparing for a massive contract to deliver all court orders, the government abruptly revoked it, dealing a near-fatal blow to the company. Quickly thereafter Polish Post, with its deep taxpayer-funded pockets, began undercutting all InPost’s bids at impossibly low prices, ensuring that Brzoska couldn’t compete fairly for any government deliveries. The Civic Platform government, led by Donald Tusk, took an active role in defending the state monopoly, forcing Brzoska to abandon letter delivery altogether.

Brzoska survived the tribulations and refocused InPost entirely on parcel deliveries, doubling down on innovation and automation. Today, Brzoska stands as one of Poland’s most celebrated entrepreneurs, with an estimated net worth of $1.3 billion.

Regicide

Mentzen’s moment had come.

As Janusz Korwin-Mikke neared the age of 80, his hold on the party began to slip. In 2019, he formed an alliance with the nationalist movement and a few minor, mostly obsessively antisemitic parties, rebranding the coalition as Konfederacja (Confederation). Against expectations, it entered Parliament, and within this new movement, a new star began to outshine its old leader.

As Mentzen’s popularity grew, the party underwent a meticulously engineered transformation. Potential rivals—those who might have challenged his dominance—were systematically pushed out. The party ranks were purged of competition, leaving only one man standing as Korwin’s natural successor.

Then came the regicide.

Sensing his fading control, Korwin struck a deal before the 2023 party convention. He would retain the honorific title of party founder, with some influence over ideological direction, while Mentzen would take over as leader. But the moment Mentzen secured victory, he moved swiftly. He invited Korwin’s most prominent enemy to speak, signaling a new era. As the speech began, Korwin, visibly distressed, limped out of the convention hall and hid in the bathroom. A year later, after a devastating election loss, he was blamed for the failure and cast out entirely.

The king was dead. Long live the king.

With the throne secured, Mentzen turned his focus to true power. He had already won over the far-right, but now he needed mainstream recognition. Following Jordan Peterson’s advice, he first “got his room in order.” He distanced the party from its most toxic elements. He softened its rhetoric. He moved toward the political centre.

But who was Mentzen beneath all the political maneuvering and the carefully crafted marketing image? Was he an anarcho-capitalist, hiding behind strategic pragmatism like Milei? A businessman seeking financial gain through politics? Neither. At his core, Mentzen was and remains a radical conservative who supports some free markets and some deregulation—but only where it suits his vision of entrenching radical traditionalism in Polish society.

He wants to simplify the tax code, but dreams of imprisoning the youth behind the barbed wire of military garrisons. He champions freedom of speech, but wants to prosecute all speech criticizing the Catholic Church. He supports budget cuts—except for state agricultural subsidies, and holding onto many of the state owned enterprises. He wants to legalize weed, but he would not mind theocracy encroaching itself in Polish government, and the state proclaiming that Jesus is the King of Poland. He advocates for free markets—yet has never read Ayn Rand and never talks about Austrian economics. The bookshelves in his home are filled with works of anti-libertarian conservative thinkers. He calls for lower taxes—unless they’re tariffs, which suddenly become indispensable. He values individual liberty—unless you’re gay, in which case you are a threat to Polish society.

Mentzen is an unusual blend of classical liberalism and reactionary conservatism. He sees capitalism as a means to build a strong, deeply traditionalist Poland. When liberty and conservatism clash, liberty is the first to be sacrificed. And when he declares, “I am not a libertarian,” he is being entirely honest.

Yet, whatever one thinks of his ideology, his political acumen is undeniable. Last summer he announced his run for president. Mentzen channelled a substantial portion of his €10 million fortune into the campaign. The reaction was sceptical, even among his usual sympathizers. Nevertheless, in just a year, he surged through the polls, rising to third place, posing a real threat to the Polish political establishment.

Today, polling aggregates place Mentzen at 17%, conservative candidate Karol Nawrocki at 22%, and left-centre Rafał Trzaskowski at 35%. Poland’s long-standing political duopoly could be on the verge of disruption. If Mentzen sneaks into the second round, the political landscape could shift dramatically, bringing down the old party divide. Some polls even suggest he has the strongest odds of winning the presidency if he makes it into the second round, picking up some of the middle-ground voters in such a scenario.

Up until now, Mentzen has had a near-monopoly on free-market rhetoric in Polish politics.

Burial of the Hatchet?

But here, Brzoska enters the scene.

On February 10th, Donald Tusk, who returned to reign Poland as the prime minister after a decade of conservative rule, hosted a conference titled A Breakthrough Year at the Warsaw Stock Exchange. Seated in the front row, among Poland’s business elite, was Rafał Brzoska. For the first hour, the event followed a predictable rhythm. Tusk presented favourable statistics, projected economic growth, and spoke in generalities. Then, in an unexpected turn, he looked directly at Brzoska and said:

“I have read interviews with Rafał Brzoska where he said that deregulation is not difficult, it just requires willingness, and that he knows exactly what needs to be done. Well, then he should get to it. If you could quickly prepare recommendations for changes that do not require legislation…”

To which Rafał Brzoska answered:

„Challenge accepted.”

Out of a sudden Brzoska entered the world of politics. The scene played out as if it were a spontaneous exchange, albeit it was likely orchestrated in advance. Within days, the SprawdzaMy initiative— meaning We Call [seemingly the PM’s bluff] —was up and running. The deregulation team, assembled under this brand, began collecting proposals to streamline Poland’s economy. Any citizen can submit ideas. Free-market advocates were particularly enthused by the inclusion of Prof. Robert Gwiazdowski, one of Poland’s most outspoken champions of economic liberty, although the rest of the line-up seems much more party-driven.

But why had Tusk, long a centrist pragmatist, suddenly pivoted toward capitalism? It seems to be an almost haphazard scramble to counter Mentzen’s meteoric rise to popularity rather than a deeply held conviction. The international ripple effects of Milei’s victory in Argentina, coupled with the DOGE’s budget scrutiny seen in Trump-era America, likely played some role as well. Whatever the reason cutting lard is now a sufficiently sexy idea to pay lip service to in Warsaw.

Mentzen’s advocacy for deregulation had also forced his two main presidential competitors to follow suit. The ruling party’s candidate had begun parroting free-market slogans, proposing even cautious welfare cuts. Meanwhile, the conservative candidate — a former boxer with ties to neo-Nazis and organized crime, alleged by some journalists to have worked as security guard in a brothel —also shifted his messaging, swearing he would never sign a law that increased taxes.

While today in Poland free markets are in the air, it is not certain they will materialize into any legislative reform. The real intrigue centres on Brzoska. What is his endgame? Is he interested in party politics, leveraging his business status for political capital? Or is he driven by the free market zeal, determined to prevent Poland from slipping back into socialist stagnation?

My cautious guess is that Brzoska is entirely serious about reform. And his actions may carry an element of personal vengeance. The state apparatus, under Tusk’s previous government, nearly destroyed him. Now, as Tusk postures for votes with pro-market gestures, Brzoska will be dead serious about pushing his policies through. If Tusk doesn’t get it done all hell could break lose, with the billionaire, going for the jugular.

Brzoska might not hesitate to turn against him. If economic reforms stall, he could even align with Mentzen. Poland could find itself in a rare polarization spiral—one that advances economic freedom. The three major parties might start accusing each other of not deregulating fast enough, each vying to appear as the true budget hawk. For the first time in modern Polish history, political polarization could drive the country toward greater economic freedom rather than welfare expansion. It all depends on just how committed the two millionaires are to the philosophy of free markets.

This piece solely expresses the opinion of the author and not necessarily the magazine as a whole. SpeakFreely is committed to facilitating a broad dialogue for liberty, representing a variety of opinions. Support freedom and independent journalism by donating today.