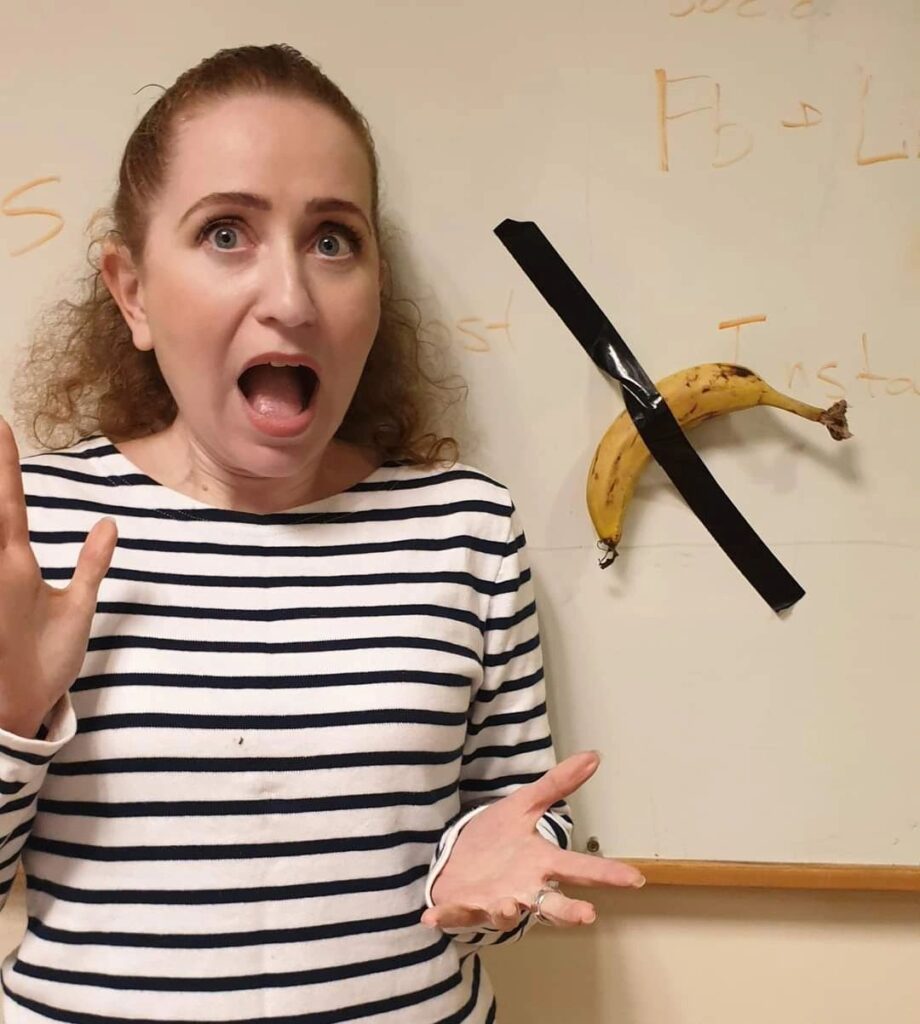

Maurizio Cattelan’s Comedian, a banana duct-taped to a wall, has once again made headlines, this time for selling at auction for a staggering $6.2 million in November 2024. Initially debuted at Art Basel Miami in 2019 and sold for $120,000 per edition, the artwork’s latest sale reaffirms its position as one of the most polarizing yet fascinating examples of contemporary art.

To many, the $6.2 million price tag feels like the punchline to an ongoing joke about the absurdity of art markets. Critics mock the piece as a symbol of wasteful indulgence, a banana—destined to rot—representing little more than a frivolous expense for the ultra-wealthy. However, when examined through the lens of Austrian economics, Comedian becomes far more than a controversial artwork. It offers a profound lesson about creating and exchanging value in a free market.

As Austrian economists Carl Menger and Ludwig von Mises argued, value is subjective. It is not determined by intrinsic properties, production costs, or even the artist’s intent but by preferences, perceptions, and judgments of the individuals. The journey of Comedian, from its initial $120,000 sale to its $6.2 million valuation, exemplifies this principle. The artwork’s worth lies not in the banana or the duct tape itself but in the unique circumstances surrounding its creation, its cultural resonance, and the market forces that have propelled it to notoriety.

To understand why Comedian was worth $6.2 million to its buyers, we must first recognize that its value was never about the banana itself. The production cost—a mere dollar or two—is irrelevant. The value came from other factors that Austrian economists would recognize as critical to market dynamics:

- Concept and Narrative: Comedian is a statement about the absurdity of art markets, a provocation to traditional definitions of art. As Cattelan himself noted, “Wherever I go, I am always asked for a selfie, so this banana is meant to be a self-portrait.” Its simplicity invites interpretation, debate, and cultural engagement—intangible qualities that collectors found worth paying for.

- Scarcity: Only three editions of Comedian were sold, making it a limited commodity. Scarcity, a key driver of market prices, played a significant role in its value. The exclusivity of owning one of only three pieces created strong demand among high-profile buyers.

- Reputation (the “Brand” of the Artist): Cattelan’s reputation as a provocative artist added immense value. Known for works like the solid gold toilet America and a controversial sculpture of Pope John Paul II struck by a meteorite, Cattelan has built a brand around audacious and satirical art. His name alone carries cultural and monetary weight, much like a luxury brand.

- Context and Prestige: The piece was displayed at Art Basel Miami, one of the most prestigious art fairs in the world. This association added legitimacy and allure to the artwork, creating a perception of value that would not exist if the same banana were taped to a wall in a local grocery store.

- Media Hype and Publicity: The virality of Comedian—fueled by memes, news coverage, and heated debates—amplified its value. As Ludwig von Mises observed, reputation and perception are crucial to determining market prices. The more attention Comedian garnered, the more desirable it became.

Critics often decry such examples as evidence of market irrationality, claiming that the art market, like many other markets, is governed by hype, speculation, and manipulation. What they miss is that these factors are not market failures—they are the market. Just as the subjective valuations of buyers and sellers set the price of any commodity, the same forces determined the price of Comedian.

The principles of Austrian economics offer a clear explanation for the $6.2 million banana. In Principles of Economics (1871), Carl Menger established that value is not inherent in an object but is instead determined by its ability to satisfy human wants. Ludwig von Mises expanded on this in Human Action (1949), arguing that prices emerge from the interaction of subjective valuations in a market.

From this perspective, Comedian’s price is not irrational but entirely logical. It reflects the subjective preferences of buyers who valued the artwork for its concept, exclusivity, and cultural significance. These buyers willingly exchanged their money for the ownership of a piece they believed was worth the price—no coercion or government intervention was involved.

This highlights a key libertarian principle: markets work precisely because they allow individuals to make their own decisions about value. Governmental attempts to dictate what something “should” be worth— be that through price controls, regulations, or subsidies—inevitably distort markets and lead to inefficiency.

Cattelan’s banana may be an extreme example, but it serves as a microcosm of how subjective value operates across all markets. Consider Bitcoin, another example often dismissed as absurd or speculative. Like Comedian, Bitcoin’s value is not tied to its production cost or inherent utility but to its scarcity, trust, and the greater narrative. In both cases, value is determined by individuals making voluntary exchanges based on their own preferences.

Critics often claim that free markets lead to “bubbles” or inefficiency, but history shows government intervention creates far greater harm. Laws like Certificate-of-Need (CON) in the U.S. restrict hospital supply, driving up prices and reducing access, while drug patents grant monopolies that allow companies to overcharge for life-saving medications. These interventions limit competition and harm consumers, whereas free markets foster innovation and regulate behavior through competition.

What Comedian ultimately reveals is that value cannot—and should not—be dictated by authorities. In a free society, individuals have the right to determine what they value and exchange their resources accordingly. This principle, central to libertarian thought, underpins both cultural and economic freedom.

Critics who mock Comedian miss the irony: the banana’s value lies in its ability to challenge assumptions about art and markets. Similarly, critics of free markets fail to see that subjective valuations are what drive innovation and prosperity.

Cattelan’s banana, taped to a wall, may seem absurd, but it serves as a mirror for society’s economic behavior. Whether it’s a $6.2 million artwork or a $98,000 Bitcoin, subjective value and voluntary exchange are what make markets—and the people within them—truly free.

In a world where governments often intervene to impose their notions of value, Comedian reminds us of an essential truth: it’s not the material that matters, but the perception. As Austrian economics teaches us, value is created by choice, not dictate—a principle that sustains both free markets and free societies.