Urban explorers are the 21st century voyagers, marauders, and pioneers, who delve into exploration steered only by the principle encapsulated by Ayn Rand in: “The question is not who is going to let me; it is who is going to stop me.” As they bask in the shadows of rusting away factories, inhale dust from close-to-collapse mines, roam through rodent-filled sewers, and charge through once-ripe-with gunpowder military bunkers, they often find themselves in the moral grey area of accepted social norms regarding the property rights.

Those adventurers are often driven by contestation of the status quo, and willingness to transgress the human-made environment; yet, one cannot pin a single political motivation on their exploration within sites off-limits to the public. In his tome Explore Everything, anthropologist Bradley Garrett wrote: “Urban explorers know and love cities inside and out (…) and disregard… what is socially expected or acceptable. The libertarian philosophy behind much of the motivation is not to be mistaken for progressive politics. (…) ‘I would not like to associate, for instance, with a group who protests against the waste of empty space in prime locations. I don’t think we are against the system, we are just pointing out its limits.’”

The spectrum of existing practice spans from the absolutely reckless behaviour of certain UE practitioners – such as Ally Law, whose undertakings typically result in an encounter with the police – to quite low-key and reasonably calculating-risk expeditors who never experience a pair of handcuffs on their explorations. Ethical boundaries of the activity are also subject to often quite heated debate in the community. For the last three years, since I began sauntering into the abandoned as a the hobby, I have given serious thought to the ethical implications of that practice in a libertarian worldview. As I was delving into the world of rust, decay, and cobwebs to emerge as a full-grown cataphile mole-man, I was ecstatic to discover that urban exploration has a precedent in libertarian literature, in the work of one of the mothers of libertarianism herself, Ayn Rand.

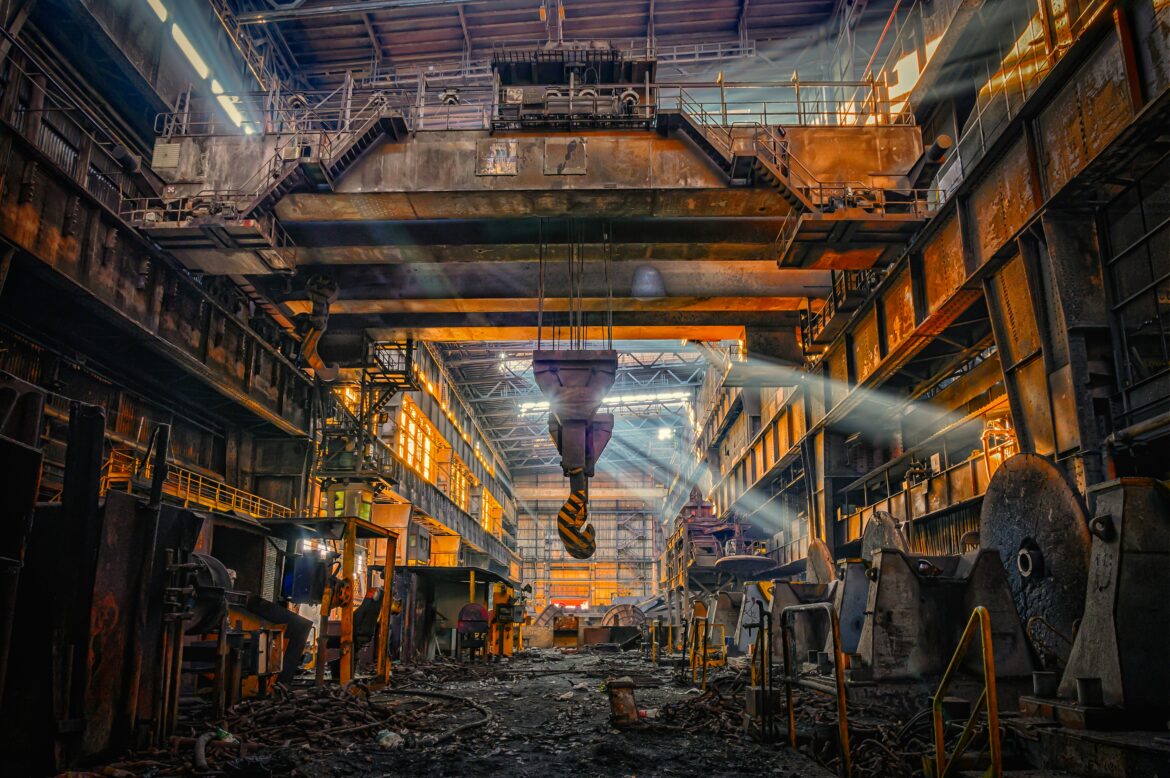

“They had driven across Michigan to the ore mine. They had walked through the ledges of an empty pit, with the remnants of a crane like a skeleton bending above them against the sky, and someone’s rusted lunchbox clattering away from under their feet. She had felt a stab of uneasiness, sharper than sadness”

– Atlas Shrugged

Hank Rearden and Dagny Taggart, clear protagonists of the dystopian novel, spend a whole month of their scarce holiday driving through the Northern states in search of the remnants of the once-thriving industry. They enter abandoned mines, walk through ghost towns, and spend long hours inside factories in a state of severe putrefaction. Not only are they not disparaged for their breach of property rights, but their urban exploration is rewarded with the crucial discovery of a motor prototype with the potential to turn around the slowly degrading world economy.

“When she walked through the silent yards—where steel bridges still hung overhead, tracing lines of geometrical perfection across the sky —her only wish was not to see any of it, but she forced herself to look. It was like having to perform an autopsy on the body of one’s love. She moved her glance as an automatic searchlight, her teeth clamped tight together. She walked rapidly—there was no necessity to pause anywhere. It was in a room of what had been the laboratory that she stopped. It was a coil of wire that made her stop. The coil protruded from a pile of junk.”

Are Hank and Dagny committing some sort of immorality when they enter someone’s private property? It seems that the issue at hand treads into the very delicate area of the difficult to judge edges of property rights. This is fairly typical of many points of libertarian doctrine. The non-aggression principle allows you to defend yourself from aggression, however, the force applied in response or the probability of the threat which allows you to begin self-defence is naturally murky, especially since the circumstances rarely allow for long considerations. Exact boundaries around the property are at times nebulous. A libertarian has to draw a distinction between three different categories of property involved in urban exploring.

First, we have locations, which once have been privately owned but are now abandoned. Thus, they are by definition devoid of property rights. There is no owner whose rights are infringed upon by the explorer’s presence in a particular area as he has given up that property, by ceasing to exist or by abandonment.

During my explorations, I have encountered a lot of property without anyone to whom it could belong. In Luxembourg, one can visit ruins of an artificial castle, once a residence to an oil magnate, who upped and left the country twenty years ago and never returned – he died in Saudi Arabia and no heirs ever seized the property. In such a situation, an exploration of the deteriorating residence is a harmless activity. No one’s rights are infringed as there is no owner of the place, and a visit, which does not alter the place, is perfectly acceptable under libertarianism. Indeed, most urban explorers adhere to the modus operandi: ’’Take nothing but pictures. Leave nothing but footprints.” Hence an exploration remains in line with a libertarian view of property rights.

Yet, it is often hard to judge which property is completely abandoned. It could be well into a state of decay and still have a rightful owner. If no heirs showed up to the castle for twenty years, it would seem reasonable to operate under the assumption that it is unowned. At times such suppositions will fail. The world of urbex is one lavish with grey areas and often hardly visible fine lines. Ethics of urban exploration fall under a broader question – who should be allowed to seize unowned property? Who has a moral right to claim ownership of a piece of land on the moon? Who can settle on some piece of land in the jungle undefiled by humans ? Who should decide how to deal with a claim-free property? Lockean concepts of property rights suggest that since no one was doing anything with the resource, no consent was required to claim ownership, therefore the initial claim of ownership and all subsequent ones are legitimate. So it seems that explorers who enter the abandoned do not anything unethical.

In Atlas Shrugged, we learn that the decaying factory after the bankruptcy was transferred to the bank, which left it in a state of decay. Perhaps Ayn Rand thought that the property was effectively abandoned by the bank as it was destroyed and looted, and no attempts to restore the factory were likely. Such a common sense conclusion has to be reached in the cases of many slowly deteriorating locations.

A reader could at this point remark that there are no properties without an owner, as the state immediately gains ownership of any abandoned resources. Indeed, in most cases, once someone dies without any inheritors, their assets are appropriated by the state. This leads to the second category which is property under the control of the government.

Libertarians recognize the malicious nature of government activity, echoing Friedrich Nietzsche’s statement that: “The state lies in all languages of good and evil; whatever it says it lies; whatever it has it has stolen.” Indeed, all government property is a result of extortion. Individuals within a society paid a heavy price for the state to own all its infrastructure. The reality remains that all public goods are stolen. As such, they lack clear legitimate owners. When I juggernaut through the abandoned bunkers in the Maginot Line, I do not harm the French residents, who ninety years ago paid $3.7 billion to build this grand monument to the failure of the government. It seems we have a right to use, in a non-destructive way, a particular public good. No individual is a victim of treading on some rust-ridden state-owned factory. No aggression occurs when people decide to enter, against the state’s wishes, an abandoned mine. The decision to walk through the sewers beneath a city requires little moral quandary when made by a libertarian.

And last, we have buildings in active use, where no permission for entrance was obtained. Many urban explorers enjoy climbs onto skyscrapers and corporate offices or even infiltrate factories in active use. Very little moral leeway can be applied in such scenarios. Those instances have clearly set-out property rights, which require either explicit or implicit consent to enter. In most cases, none is given to the explorers, and their action is an outright breach of the non-aggression principle. Not only are the rights of the private owners not respected, but the risk exists of costing them a significant amount of time and stress if the proprietor has to run around his possession evicting undesired intruders.

”The room looked as if it had been an experimental laboratory—if she was right in judging the purpose of the torn remnants she saw on the walls: a great many electrical outlets, bits of heavy cable, lead conduits, glass tubing, built-in cabinets without shelves or doors. There was a great deal of glass, rubber, plastic and metal in the junk pile, and dark gray splinters of slate that had been a blackboard. Scraps of paper rustled dryly all over the floor. There were also remnants of things which had not been brought here by the owner of that room: popcorn wrappers, a whiskey bottle, a confession magazine. (…) she was covered with dust by the time she stood up to look at the object she had cleared. It was the broken remnant of the model of a motor. Most of its parts were missing, but enough was left to convey some idea of its former shape and purpose. She had never seen a motor of this kind or anything resembling it.”

In the end, Urban Exploration not only gives a direct and tangible insight into the past but also allows one to see how the future can turn out to be if we fail at the preservation and expansion of our liberties. If the government is to successfully strip away our freedoms and take further control over the economy, we might see the world transform into a desolate wasteland. The vision of ghost towns, abandoned factories, and ravaged railways from Atlas Shrugged is a threat difficult to dismiss as unrealistic.