It may be difficult for some to imagine a place for firearms in the sanitised, hyper-organised societies in which we live today. For a long time, we have entrusted the State with the preservation of our safety, security and basic liberties. Government is a protector, not a repressor, after all.

However, the rules-based democratic societies we take for granted may be built on fragile foundations. In recent years, many promising reforming states have regressed towards authoritarian systems of government before our eyes.

Turkey, once touted as a model of democratisation in the middle east, is among the number of major states which has turned towards repressing its own citizens. For proponents of individual rights, this is concerning. For Armenians, however, this is déjà-vu.

104 years ago today, agents of the Ottoman Government armed with a list of names and the cover of darkness, broke into 270 homes across Constantinople (Today’s Istanbul) dragging out intellectuals, businessmen, clergymen, journalists and political leaders. They would be rounded up, and summarily executed. Armenians mark this date, April 24th 1915, as the start of the Armenian Genocide.

For many members of the Armenian intelligentsia in Constantinople, these raids came as a complete surprise. After all, less than seven years prior, they had supported the Young Turk Revolution of 1908, which stripped the Sultan of his limitless power and imposed a democratic constitution.

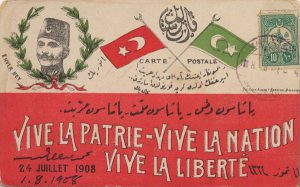

Postcard from the 1908 revolution depicting Enver Pasha and the slogan “Long live the fatherland, Long live the nation, Long live Liberty”. Enver would later become one of the chief architects of the Armenian Genocide.

Under the old Ottoman Millet system, Christians held the status of Dhimmi (infidels with State protection). In practice, however, it meant subjection to extra taxes on births, marriages, land and even deaths. Young boys would be routinely conscripted into Janissary units. Crucially, Christians were also denied the right to bear arms. With the coming of the Second Constitutional Era, Armenians now enjoyed full civil rights, as their representatives took up elected positions in the halls of the new Parliament. Their sons would now be drafted into the regular army on equal basis.

Poster depicting ethnic Armenian members of the Ottoman parliament with the slogan “Liberty, Equality and Brotherhood” written in Armenian, Turkish and French. The text at the top right reads “Long live the July 1908 Constitution”.

Unfortunately, the Ottoman Empire’s experiment with constitutional democracy would not last long. Soon, it would crumble under the weights of its internal contradictions. “Ottomanism”, the humanist ideology which treated all peoples of the vast empire as equal citizens would soon give way to Turanism – a violently nationalist ideology with the goal of uniting all Turkic peoples into a single ethno-state, free of the cosmopolitanism which had defined the Ottoman period.

In 1913, the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), a turkish ultra nationalist party, would stage a coup. As the christians of the Balkans regained their independence, the Ottoman Armenians found themselves hostages of an increasingly homogenous, and paranoid Empire.

With the outbreak of the Great War, it was not long until the Three Pashas (Mehmet, Enver and Talat Pashas), the triumvirate which ran the failing empire, began to search for a final solution to “the Armenian Question”. The Ottoman authorities increasingly came to suspect the Armenians, Greeks and Assyrians, the last remaining non-muslim minorities of the Empire, of acting as Russia’s fifth column. As the leader of an Orthodox power fighting on the Entente side, the Tsar had long made clear his divine mission to liberate fellow Christians from foreign rule.

Despite the suspicions, the Armenians of the Empire went out of their way to profess their loyalty to the Sublime Porte (the seat of Ottoman power). They continued to manage imperial finances, provided supplies for the war effort, and joined the military in large numbers.

On the Home Front, Armenians would respond to a government directive forbidding the bearing of arms by christian civilians with frenzied enthusiasm. Political parties encouraged Armenian militias to drop their weapons.

Civilians queued at military posts of local government offices to hand off their guns, swords and other weaponry. Such was their eagerness to affirm loyalty that those who did not own firearms would buy them from muslim neighbours at a premium just so they could be seen turning them over to the authorities.

These demonstrations of allegiance, as well as the bravery of Armenian soldiers on the battlefields of Sarikamish, where Enver Pasha suffered a devastating defeat at the hands of the Russians, would not be enough to appease the vengeful Ottomans. In the years following initial arrests of the Intellectuals of Constantinople, the Authorities would indiscriminately exterminate two thirds of their Armenian citizens, and march the survivors into the deserts of Syria.

The “Lambs to the slaughter” trope should not be overplayed, however. Many chose resistance. In Musa Ler, for instance, 250 fighters held off German-equipped ottoman armies for over 50 days from the cluster of Armenian villages nestled between the mountains and the mediterranean coast, until they were eventually evacuated by the French Navy. The story’s novelisation would later inspire the Jewish planners of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising.

This painful episode of Armenian history scared the survivors and their descendants for generations. For them “From my cold dead hands” became much more than a bumper sticker slogan; it came to symbolise their will to resist state repression by all means. This attitude would remain pervasive throughout the decades of Soviet rule, until the Armenian people would once more be faced with an existential threat. When that test came, they were ready.

Hundred year old Armenian lady with a rifle, Nagorno-Karabakh, 1993

Of course, In practice, few gun control initiatives immediately lead to genocide. However, recent history has shown us just how quickly unarmed, law-abiding democratic societies may descend into tyranny upon the erosion of trust in the social contract.

Frederick Douglass fundamentally understood this all the way back in 1867, when he declared “A man’s rights rest in three boxes: the ballot box, the jury box, and the cartridge box.”

This piece solely expresses the opinion of the author and not necessarily the organisation as a whole. Students For Liberty is committed to facilitating a broad dialogue for liberty, representing a variety of opinions. If you’re a student interested in presenting your perspective on this blog, click here to submit a guest post!

Image: Wikimedia