At a time when extreme and harmful nationalism is on the rise at an alarming rate, it is important to reflect on rampant nationalisms arch nemesis: Cosmopolitanism. In short, Nationalism is the belief in economic, political and social systems that support one particular nation’s interests and goals. Cosmopolitanism encapsulates an extremely broad and varied set of beliefs of political, economic and philosophical varieties. These variations of Cosmopolitanism are anchored by an axiomatic commitment to a core idea that all human beings, regardless of race, religion or political orientation are part of one single universal community, comprising of the whole of humanity.

Xenophobia throughout The Ages

Cosmopolitanism is an important development in human affairs, and racism has been a consistently brutal practice throughout history. Fear of the other has nearly always been the norm up until recently; some still haven’t shaken the dark habit of humanity’s excessive localism.

Sadly, throughout history many looked for the differences rather than the obvious congruence people possess.

Aristotle theorised that the differences between various races were determined by climates.In the western world it is cold, meaning people are hardy and tough, but lack skill and intelligence. This explained why the barbaric tribes produced great warriors and a love of freedom, but had no great temples, works of literature or art. On the opposite end of the spectrum, he theorised that the eastern world is hot, resulting in intelligent but lazy people who are naturally inclined towards the authority of another. Unlike the western people, easterners had great works of architecture, literature and art. However, they lacked a love of freedom and made paltry warriors.

This explained to the Greek mind why the east was dominated by despotic rulers. Keeping in line with Aristotle’s philosophy of virtue being found between two extremes, Greece was located between the extremes of the barbaric west and the effeminate east, thus had the virtues of both east and west but the vices of neither.

A bizarre example of xenophobia in the medieval ages can be found within the rhetoric against Jewish people, especially Jewish males. Shockingly, many in the Latin West believed that, because of Jewish people’s involvement with the death of Jesus Christ, Jewish men menstruated on Good Friday as punishment for their past sins. The idea was to depict Jewish men as weak, effeminate and morally impure, as menstruation was commonly employed as an allegory for moral impurity.

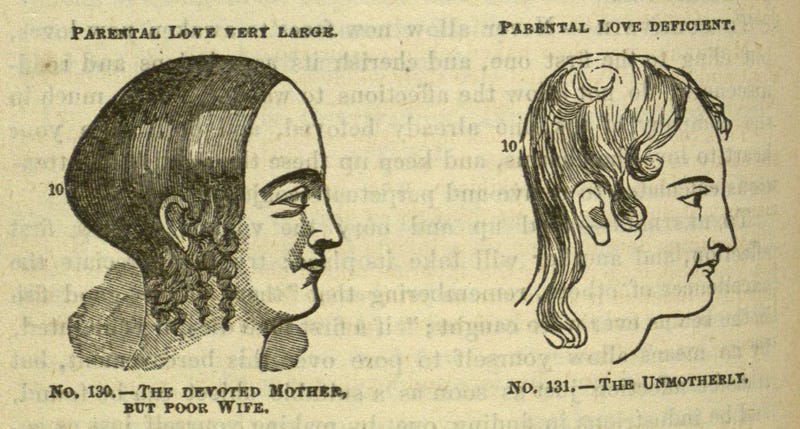

Even the Enlightenment, with its love of rationalism, science and progress, was not immune to xenophobic tendencies. In fact, rationalism and science were used to justify these tendencies. The most egregious example of this was the use of phrenology to justify racial hierarchy. Phrenology, now considered quackery, was considered a serious science during the Enlightenment. It consisted of examining the bumps and dents in skulls to deduce how the brain worked not only in general but on an individual level.

Eventually, this practice was co-opted by those who wished to justify their racism using “science”. For example, François-Joseph-Victor Broussais concluded that by examining skulls he could deduce that Caucasians were the most beautiful race, that the Maori people could never live in civil society, and that various African tribes lacked intellectual abilities.

The idea of using skulls was to show that these differences were not only skin deep, but inherent differences hardwired into people’s brains, nothing could change the dents on your skull and thus some races were destined for servitude and mediocrity while others exploited what were effectively, human beasts of burden.

The Greek origins of Cosmopolitanism

The first recorded use of the word Cosmopolitan comes from a quip from the infamous bohemian philosopher Diogenes of Sinope. Diogenes was a colourful character, living in ancient Greece during the fourth century. As one of the founders of cynic school of philosophy, Diogenes believed that all artificial practices and rules of society were contrary to human happiness. He condemned the family, property and even money, as concepts we should respect. Following this radical line of thought, Diogenes aimed to lead by example. He denied all rules of social decency, he urinated, defecated and even masturbated in public.

In Ancient Greece, Greek men were mainly defined by their relationship to their local origins, their family and their state. These three identities were essential for the self-image of Greek males. In this context, it was especially shocking when Diogenes was asked where he was from, that he quipped “I am a citizen of the world” or in the original Greek kosmopolitês, what we now call Cosmopolitan. Diogenes wished to show disdain for the conventions which separated people arbitrarily into different tribes, classes and citizenries. According to Diogenes, these conventions separated people when there were few reasons to think they were so different from one another.

In relation to this ideal of the radical similarity of humanity, another anecdotal story of Diogenes is of interest. The prodigy general and conqueror, Alexander the Great, was accustomed to the practice of respecting philosophers having been tutored by Aristotle. Surprisingly, the young king had a deep admiration for of Diogenes. Once he even stated that if he had not been born as Alexander he would like to have been born as Diogenes.

There are multiple versions of Alexander and Diogenes meeting, but a personal favourite and one related to the topic of Cosmopolitanism centres around bones. Alexander approaches Diogenes who is attentively scanning through an immense pile of human bones. When Alexander asks him what he is doing Diogenes replies “I am searching for the bones of your father but cannot distinguish them from those of a slave”.

Unlike Broussais, Diogenes saw nothing special in the skulls of the dead. The moral of the story is that there was nothing inherent within any person that made them any more or less worthy than another.

The cynic school of philosophy, which Diogenes aided in founding, importantly posited that our first and foremost form of affiliation should be to our common humanity, not our uncontrollable secondary characteristics of race, gender or class. Cynical texts remain in a woefully fragmentary state, meaning that most of our knowledge of cynicism comes from other sources discussing its tenants and not always in a positive light.

Thankfully this is not the end of Cosmopolitanisms’ journey. Influenced heavily by the Cynics, the Stoic school of philosophy continued moving toward theories not based on individual states, but on based upon a higher natural law.

The Stoic tradition

Stoicism was a school of philosophy that believed the ultimate aim of life was to live well, and that living well required moral virtue. Moral virtue can be acquired and understood by applying our reason to understand the order of the universe. From what we can gather from fragmentary texts, the Founder of Stoicism, Zeno of Citium, was not a dedicated or conscious Cosmopolitan. His student, and eventual successor, Chrysippus, became dedicated to the ideals of Cosmopolitanism due to the influence of cynic philosophers such as Diogenes.

Chrysippus ambitiously explained that since all people possess reason to understand how law ought to be, they must be part of a larger city composed of all rational beings. The unity of human rationality is a key aspect of Stoic thought.

While the early Greek Stoics were revered in their day by many, their texts also survive in depressingly fragmentary states. This means that the bulk of our extended writings on Stoicism come from later Roman authors. Primarily our knowledge of Stoicism comes from three main authors Cicero, Seneca and Marcus Aurelius.

Born outside Rome in 106BC in a place known as Arpinum, Cicero was a statesman, philosopher and orator active during the twilight days of the Republic. He was especially famous in his day for his unprecedented skills in oratory. After the Julius Caesar took power, Cicero’s political career waned and he took to writing to distract himself from the depressing state of his beloved Rome. Cicero, while not a Stoic, openly adopted some of their ethical principles and discusses Stoic tenants at length making him an excellent source from which to learn about authors whose works did not survive.

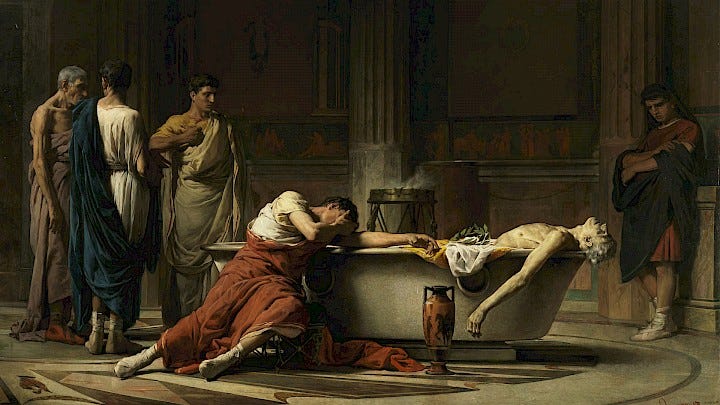

Seneca during his lifetime was a statesman, philosopher, dramatist and above all, a Stoic. He was born in 4BC and, unlike Cicero, Seneca lived under the reign of the autocratic emperors, not the Republic. Famously, Seneca was the tutor to one of Rome’s worst emperors, Nero. Seneca became Nero’s imperial advisor along with another man named Burrus. For the first few years of Nero’s reign Seneca and Burrus had immense power and influence and ruled justly, but as their influence waned, Nero took control. Seneca was eventually forced to commit suicide by his former student who believed him to be part of a plot to overthrow him.

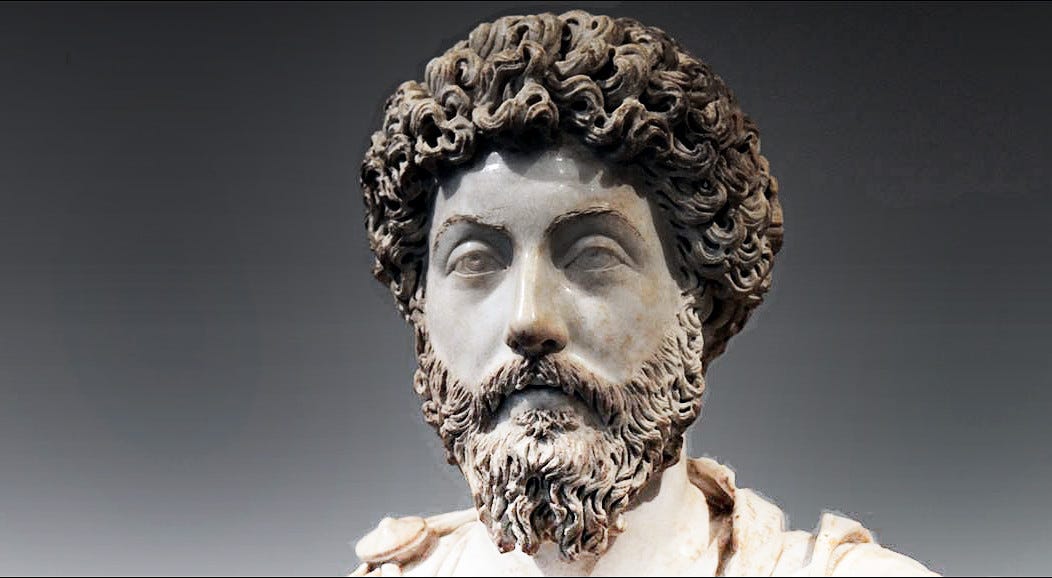

Marcus Aurelius’ reign as emperor is considered so highly, it would not be an exaggeration to claim that he came close to Plato’s ideal of the philosopher king. Sadly he was the last of the five good emperors of Rome. Born in 121AD, he reluctantly became emperor in 161AD reigning until his eventual death. While many ambitious people would jump at the position of emperor, possibly the most powerful position any one human could hold in the ancient world, Marcus had no love of power. A philosophically inclined man, he had a keen interest in philosophy especially Stoicism (however he never proclaimed himself to be a fully fledged Stoic akin to Cicero).

If there was ever a man who needed the stern attitude Stoicism demanded, it was Marcus. Large chunks of his reign were spent fighting various wars on the borders of the Roman empire.

Cicero, Marcus and to a lesser extent, Seneca were highly influential on the development of Cosmopolitan ideals which were derived from tenants of Stoic philosophy.

What makes us human?

The Roman Stoics believed that each person was special due to their endowment of reason. What makes us distinctly human is our capacity for reason, and this overarchingly dictates how we ought to treat one another.

Cicero believed that humans stood between beasts and Gods, but their rationality made them more akin to the latter than the former.“What is there, I will not say in man, but in the whole of heaven and earth, more divine than reason?” Cicero deduced that, since there is nothing more divine than reason, the Gods must have reason. Therefore, humans’ mutual sharing of reason results in a divine partnership between the Gods and humanity. There is a dash of divinity within each and every person according to Cicero.

Cicero showed that our faculties of reason were what truly defined us as humans. This meant that regardless of race, political allegiance or religious creed, all people are deemed worthy of a minimum level of respect afforded to all. Cicero writes on this topic “thus however one defines man, the same definition applies to us all. This is sufficient proof that there is no essential difference within mankind”.

Seneca in a similar vein of thought, exclaims “praise in him what can neither be given nor snatched away, what is peculiarly human. You ask what that is? It is his soul, and reason perfected in the soul. For the human being is a rational animal”.

Irrelevance of secondary characteristics

Because reason is the essence of what is essentially human, the Stoics argued that we should downplay our differences in other areas as they are deemed non-essential. Race, class and political alignment are not what make us truly human, and although they are important, they are not essential to our identity as rational beings worthy of respect.

This is how Stoicism could garner a wide variety of adherents. Birth and lineage didn’t matter didn’t matter whether you are the former slave such as the famous Stoic philosopher Epictetus or the most powerful man in the world such as Marcus Aurelius.

Cicero believed that at birth all people were given two personas. The first represented the base features of humanity, reason, speech and the human form, while the other was unique for every individual, it contained our talents, abilities and features. Speaking of the first persona Cicero writes “everything seemly is derived from this, and from it we discover a method of finding our duty”. We all have differences in our abilities, tastes and preferences, but these need not cloud our cooperation as long as we follow Cicero’s aptly put advice that “each person should hold on to what is his as far as it is not vicious, but is peculiar to him, so that the seemliness we are seeking might more easily be maintained”.

Marcus says that part of his education was learning to be impartial and non-partisan “not to be green or blue partisan at the races, or a supporter of the lightly or heavily armed gladiators at the circus”. Even as the Emperor of Rome, Marcus understood his allegiance to a higher order than the state of Rome. This did not lead him to abandon his loyalty to Rome, instead he stated that “my city and my country, as I am Antoninus, is Rome; as I am a human being, it is the world”. Marcus understood that the circumstance of birth and the bias of familiarity naturally aligned him with Rome, but his true allegiance was reserved for the whole of humanity.

This non-partisanship stretches into all aspects of life as we all live within the same interconnected world.“Constantly think of the universe as one living creature, embracing one being and soul; how all is absorbed into the one consciousness of this living creature; how it compasses all things with a single purpose, and how all things work together to cause all that comes to pass, and their wonderful web and texture.

Some people might read this and start to get nervous. An Emperor stating his allegiance to humanity sounds like a recipe for one world government. However, the Roman Stoics were not arguing for a one world government, instead they were merely arguing that our allegiance is owed ultimately to humanity as a whole, not to our individual states. All of the Roman authors I have listed were deeply politically engaged in their time and none ever made a case for a one world government. Instead these Cosmopolitan thinkers believed that one could be a patriot to one’s country while still owing allegiance to humanity.

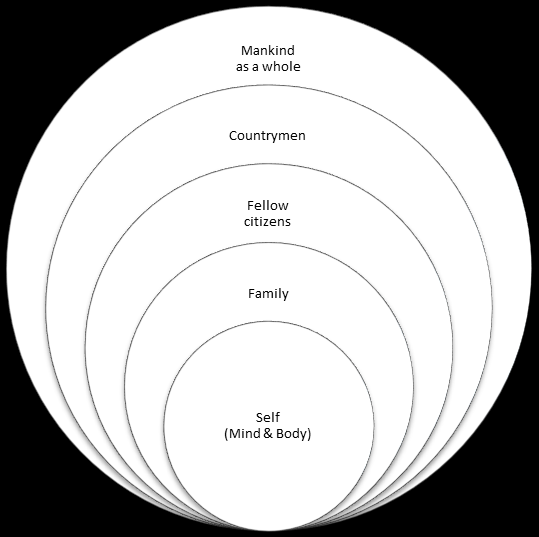

Following the teachings of Hierocles, Cicero adopted an idea of oikeiosis, a process of making something one’s own. Through this process of oikeiosis children realize they are an individual, thus they begin to care for themselves. This process continues as they mature. Slowly the child realize that their immediate family is their own. Therefore, they take it upon themselves to care for their family as well as their own wellbeing. This process continues until the whole of humanity is encapsulated by ever expanding circles of familiarity that we create. Cicero encapsulates this point by quoting the comic poet Terence’s line “I am a human being; I think that nothing human is alien to me”.

Cicero believed one could always serve humanity best by aiding those who are closest to you, “human society and its union will best be preserved if your acts of kindness are conferred upon each person in proportion to the closeness of their relationship to you”. However, this does not mean we have no duties towards people with whom we are directly connected, the wider society.

Cicero believes at a very minimum, that we should not harm others and that we should be generous within our limits to strangers in need. Seneca thought that we could serve two republics simultaneously, the particular place of one’s birth and wider humanity. But unlike Cicero, Seneca argues we should not only refrain from harm but promote the good of others irrespective of familiarity.

Universal law

This endowment of reason does not only affords us rights, but also creates a sort of universal brotherhood. Marcus Aurelius described this concept most effectively. He begins with the premise that all human beings share reason which aids us in dictating how we should act towards one another. If reason regulates human conduct, it is similar to law which has the same function. Those who live under the same law are called citizens. If law, and reason are the same, each human lives under the “law” of reason.

Since people living under the same law are citizens, each and every rational person is a citizen of the world. According to Marcus, we are all Cosmopolitan by our very nature as people, “it makes no difference whether a person lives here or there, provided that, wherever he lives, he lives as a citizen of the world”.

Cicero echoes similar sentiments arguing that “we are all constrained by one and the same law of nature”. This law of nature was non-negotiable, “there will not be one such law in Rome and another in Athens, one now and another in the future, but all peoples at all times will be embraced by a single and eternal unchangeable law”. Seneca argued the nature of humanity was “truly great and truly common” and that it is not limited by “neither to this corner nor to that, but measure the boundaries of our nation by the sun”. Above all, the Stoics believed that our duties to humanity go beyond the convention of borders due to the depth of our common humanity.

Why does this matter?

In a purely historical sense Stoicism was a major influence upon the Western world. Importantly, the universal nature of humanity present in Stoicism was adopted by Christianity which came to dominate European religious life. Cicero’s De Officiis (On Duties) was among one of the most widely read books in the European world up to the 19th century.Intellectuals of all persuasions were in one way or another familiar with Cicero’s work so much so that in seminal texts such as Adam Smith’s The Theory of Moral Sentiments. Indebted to his Christian Stoic professor Francis Hutcheson who also lectured David Hume, Smith admired Marcus Aurelius due to Hutcheson’s noontime private lectures on Stoicism. Within The Theory of Moral Sentiments Smith refers to Marcus Aurelius as “the mild the humane, the benevolent Antoninus”. The famous philosopher Kant who wrote one of the finest treatises on Cosmopolitanism entitled the Perpetual Peace was heavily influenced by both Cicero’s De Officiis and Marcus Aurelius’ his teachings found within his diary entitled Meditations.

These ideals of Cosmopolitanism are worthy because of what they aspired to achieve: a universal understanding of humanity coupled with a deep respect of all rational beings. The Roman Stoics’ views on the universality of humanity were sadly, in the minority, when it came to contemporary philosophical thought. The value of the Stoics’ philosophy may not have been reflected in its popularity but it remained undiminished and compelling. As Marcus Aurelius opined “does an emerald lose its quality if it is not praised?”Happily, their beliefs were readily available for later thinkers to adamantly make the case for a Cosmopolitan future. A case which is as compelling today as it ever has been with divisive nationalism on the rise at a time when global challenges like the impact of climate change demand a universal level of cooperation across all humanity.

This piece solely expresses the opinion of the author and not necessarily the organisation as a whole. Students For Liberty is committed to facilitating a broad dialogue for liberty, representing a variety of opinions. If you’re a student interested in presenting your perspective on this blog, click here to submit a guest post!

Image: Raius