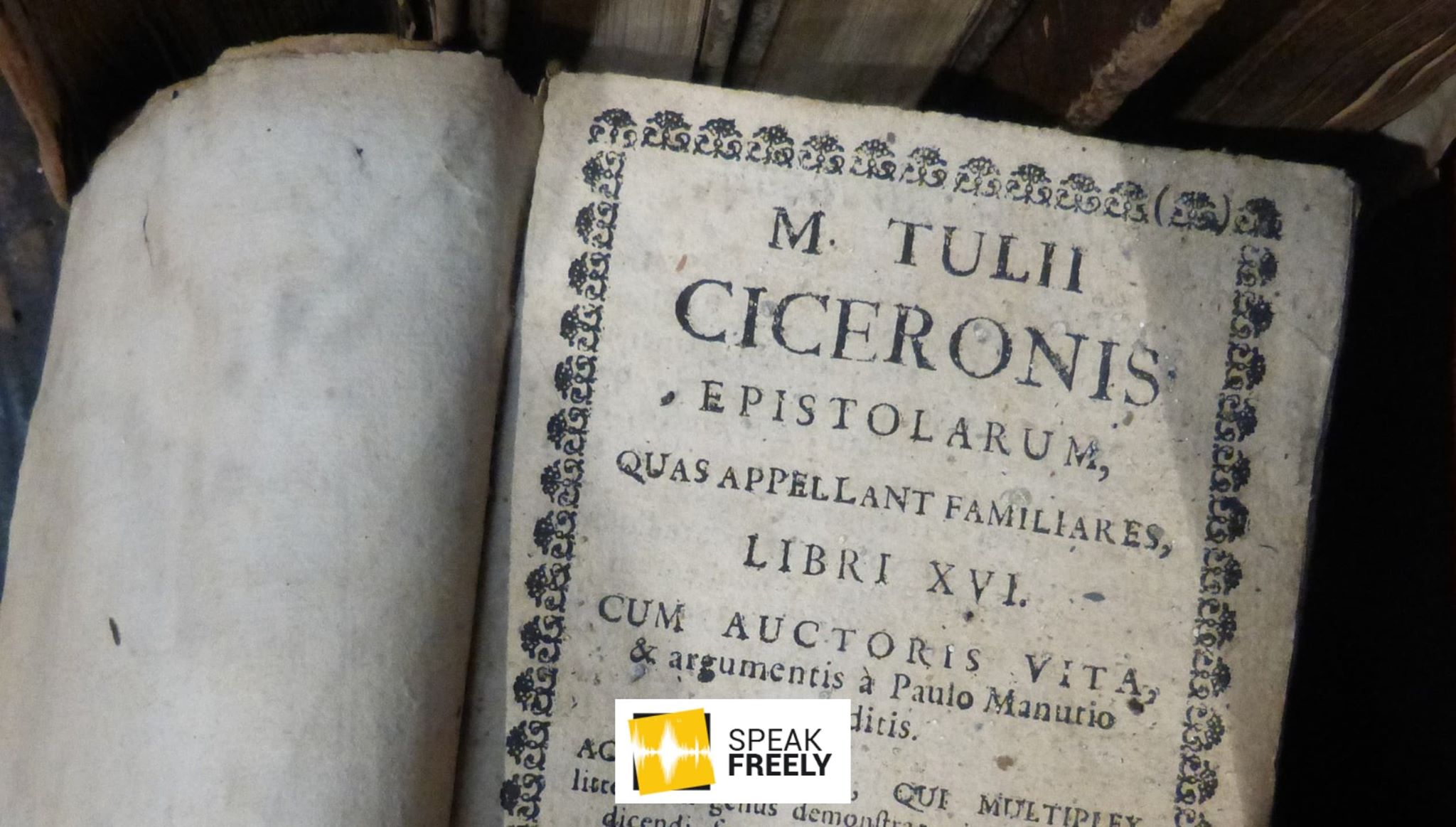

Cicero was a renowned Roman orator, statesman and writer. He was an enemy of one man rule and a self-described constitutionalist. During the turbulent twilight of the Republic he attempted tirelessly to establish a lasting peace in order to preserve his beloved republican government. Following the death of his daughter Tullia and his exile from political life, Cicero wrote voraciously to distract himself from despair. His reputation as an eloquent enemy of tyranny has been applauded by many influential people throughout history.

Admirers of Cicero in history are in no short supply. He was praised throughout the Western world for over a millennium by all sorts of people. To stress his continued relevance in the world I will have to limit myself to the praise bestowed upon him by three of the early American presidents. The Founding Father John Adams wrote that, “as all the ages of the world have not produced a greater statesman and philosopher united in the same character, his authority should have great weight”. Fellow Founding Father Thomas Jefferson dubbed Cicero “the father of eloquence and philosophy”. Finally, John Quincy Adams dramatically stated that “to live without having a Cicero and a Tacitus at hand seems to me as if it was a privation of one of my limbs.”

Cicero’s influence on the world has been immense, but in recent years he has sadly been pushed aside to an extent. Cicero is rarely read today, except by students of Classics and Latin. However, to understand the history of political thought, Cicero is an invaluable resource. Even if Cicero did not command historical clout, it would still be worthwhile to read his works. He naturally commands gorgeous prose, employing it to put forth a grounded approach to ethics. In my opinion, Cicero’s greatest achievement is his attitude towards natural law which can be seen as the foundation of later European natural law theories on the concept of inalienable rights.

What is Natural Law?

It is worth asking at this point, what exactly is natural law and why does it matter? Natural law is a term that generally creates a lot of confusion, as the term on its own is quite vague. Many people at first believe that natural law means ‘survival of the fittest’ or similar Darwin-esque phrases. Simply put, natural law can best be described as a system of ethics that derives moral standards and rules from the observable world and human nature. A key part of natural law is the idea that laws should be universally applicable and eternally relevant to human affairs.

Cicero’s View of the Universe

Cicero’s view of the universe was deeply informed by the Stoic philosophers. He did not believe literally in Roman religious myths, but justified taking part in Roman religion on the grounds of utility and respect for tradition. Cicero instead was influenced by the Stoic philosophers, who believed that there was a rational and divine order that governed the universe. In his famous book from De Re Publica, later entitled The Dream of Scipio, Cicero described how all human souls are bestowed upon humans by the divine reason of the universe.

The mark of divine intelligence upon all things is law; Cicero stated that “law is not a product of human thought, nor is it any enactment of peoples, but something eternal which rules the whole universe by its wisdom in command and prohibition”. These divine or natural laws were eternal, immutable and universally applicable. Cicero emphatically wrote, “nor is it one law at Rome and another at Athens, one law today and another thereafter; but the same law, everlasting and unchangeable, will bind all nations and all times”. This divine law can be seen implanted on all things, bestowing upon them a divinely ordained purpose and function.

Cicero’s View of Humanity

According to Cicero, by understanding something’s structure, purpose, and function, one could understand how things ought to behave. Cicero believed that humans are uniquely favored by the divine order of the universe. This divine nature is reflected in the endowment of humans with the intermingled faculties of reason and speech.

Unlike other creatures, humanity is distinctly rational. Cicero believed that reason is humanity’s most important faculty, as it enables us to perform three key functions. Firstly, it allows us to have memory, so that we can learn from mistakes and use the past as a resource to aid us in current predicaments. Secondly, reason enables us to moderate our behavior. Thirdly, and most importantly according to Cicero, we have an urge to search for the truth. Cicero stated that, “above all, the search after truth and its eager pursuit are peculiar to man”.

As an orator, Cicero understood how essential communication was, not only in politics, but in all aspects of life. Cicero referred to speech as “the queen of arts”. Speech is an essential aspect of communal living, as it enables us to learn from others and persuade people to cooperate. Cicero described speech as “this which has united us in the bonds of justice, law, and civil order, this that has separated us from savagery and barbarism”. Speech was to Cicero a sign of humanity’s inherently communal and cooperative nature and one of our greatest tools in creating a prosperous life for ourselves.

Divine Sharing of Faculties

According to Cicero, the endowment of humanity with divine reason unites all people within a single world commonwealth. Each human has two personas, one which is universal to all and another which is specific to each individual.

Cicero described the first persona, writing that “one is common, arising from the fact that we all have a share in reason”. This persona represents our common humanity which entitles every person to dignity and respect; “thus however one defines man, the same definition applies to us all. This is sufficient proof that there is no essential difference within mankind”.

The second persona with which everyone is endowed is entirely unique. Each person has different strengths, weaknesses, and tastes. Cicero suggested that this is not a reason for strife; instead he suggests that we should all do what suits us best so long as we do not harm others. He advised that “each person should hold onto what is his as far as it is not vicious but peculiar to him, so that seemliness that we are seeking might more easily be attained”. The belief that every human contains a dash of divinity in the form of their divinely ordained faculties makes Cicero’s philosophy robustly individualist at its core.

Humanity’s Communal Nature

Political theorists such as Thomas Hobbes believed that political communities were born of people’s mutual fears and anxieties. According to Hobbes, the first humans united to ensure safety from what he dubbed “the war of all against all”. Out of fear and a desire for self-preservation, they agreed as part of a social contract not to inflict harm upon one other. In Cicero’s day, the skeptic Carneades held views similar to those of Hobbes. Akin to Hobbes, he concluded that justice was conventional and expedient rather than natural and eternal.

Cicero disagreed sharply with this worldview. He believed that all humanity had an affinity towards mutual affection and cooperation. Cicero asserted that, due to humanity’s natural instinct for love and friendship, justice was the reason people united, not fear and selfish benefit; “men are born for the sake of other men, so that they may be able to assist one another”. Due to humanity’s capacity for speech, Cicero intuited that humans must be by nature a communal animal that seeks the affection and love of not only his kin but all people. To Cicero, this natural instinct was at the core of human affairs.

The primacy of justice is consistently promoted throughout Cicero’s writings, but is especially prevalent in his book De Officiis, in which he wrote that “justice is the crowning glory of all virtues”. Cicero was so dedicated to the idea of justice as a guiding force in all human conduct that he even argued that gangs of thieves, when divvying up their spoils, operate within a rudimentary system of justice; “its importance is so great, that even those who live by wickedness and crime can get on without some small element of justice … if the one called the pirate captain should not divide plunder impartially, he would be either deserted or murdered by his comrades.”

Cicero’s Conclusions

Cicero came to two key conclusions about natural law. Firstly, he argued that humanity’s faculties demonstrate that we are designed to cooperate together. Political and communal life is natural and, as it secures justice, necessary for the flourishing of people. Secondly, he outlined four baasic principles of natural justice that societies ought to follow: not to attack others physically without reason; to respect both private and common property; to stick to our promises; and to be kind and generous towards others within our means.

Cicero intuited his political philosophy by examining the natural world and human nature. His attempt at understanding an eternal guiding justice has influenced countless prominent thinkers, especially in 18th century England and the early American republic, where he was revered for his forensic mind and moral character. While Cicero’s conclusions on natural law are not infallible, his work influenced an entire tradition of rights-based political philosophy.

This piece solely expresses the opinion of the author and not necessarily the organisation as a whole. Students For Liberty is committed to facilitating a broad dialogue for liberty, representing various opinions. If you’re a student interested in presenting your perspective on this blog, click here to submit a guest post!

Image: Pixabay