In his farewell address, President Eisenhower warned his listeners to be wary of “public policy becoming captive of the scientific-technological elite”. As populist backlash against the elites and technocratic establishment rages on, heading his warning, a renewal of the contract between science and society is needed now more than ever. One key thinker, who built a roadmap to free science from its elitist institutionalisation and anti-democratic tendencies, which Eisenhower believed replaced the lone scientist-entrepreneur with committee thinking, is Paul Feyerabend.

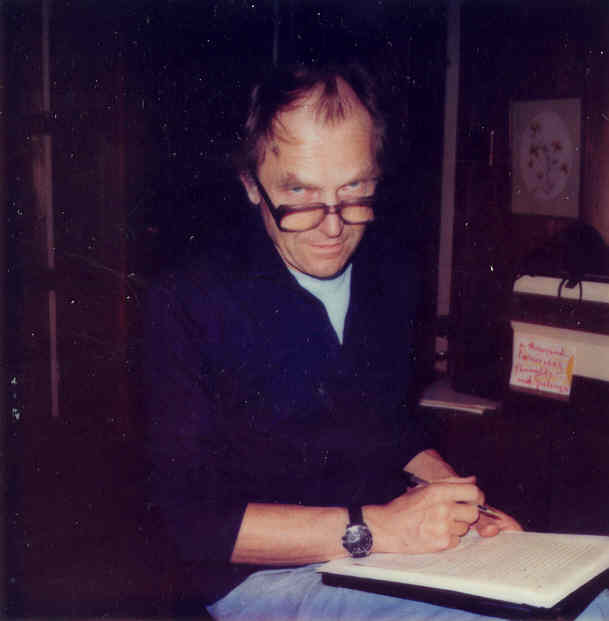

Feyerabend is an oft-neglected figure of 20th Century philosophy, but nonetheless remains of vital importance. Of the various Austrians that gifted the Anglo-Saxon world with their brilliance, his ideas are by far the most radical and challenging to engage with, yet offer us a more individualist understanding of science in society. His aphorism that “anything goes” when it comes to the scientific method has made him, in the eyes of many detractors, an enemy of science; nothing could be further from the truth. Feyerabend was a great libertarian, and a man who sought to liberate science from the tyrannical shackles of dogmatism and elitism that he saw conquer the establishment since the dawn of logical positivism.

It is important to briefly discuss Feyerabend’s philosophy of science, before arguing that it is fundamentally intertwined with libertarian belief. Feyerabend was an epistemological anarchist, believing that no single unifying source of knowledge and truth was possible. Knowledge can be arrived at through a multitude of ways, and no system or authority ought to hold a monopoly on inquiry. Mixing historical commentary with sociological insights, his magnum opus Against Method (1975) showed that scientific progress throughout history delineated nothing like the rationalist and positivist narratives that were propagated. From Galileo’s use of rhetoric far more so than empirical inquiry in defending Copernicanism, to Newton’s mystical justification for much of his physics, the view that science is the be all and end all of knowledge simply did not stand up to scrutiny.

Scientific theories were not the value-free abstractions of common belief, but rather deeply value-laden ideas. These did not just interpret the world, but shaped our language and communication of it as well. For this reason, dogmatism in science can easily descend into tyranny, and come under control of an establishment that does not permit its assumptions to be questioned. Similarly, he worried of the increasing scientism of the age, whereby scientific inquiry was viewed as the only route to knowledge. This scientism is seen in all sorts of debates on public policy today; one side claims to hold a monopoly on truth, by which means all dissent is crushed.

This is seen quite often in the “evidence-based” proposals that have become a hallmark of technocratic politics. Evidence is used not to support an argument, but rather to shape it. One example is in the recent EU EcoDesign Directive, in which studies were cited to support the restriction of hand-dryer use in public places. One of the studies conducted involved people placing their hands in a vial of bacteria and then drying them to prove that hand-dryers spread bacteria. The absurdity of such a notion, since people wash their hands, and at the very least don’t dip them in vials of bacteria, before drying, means this study has no practical conclusions to offer. The fact that the study was conducted, and resulted in policy citations, shows the means by which scientism can capture policy. The data itself reveals nothing about policy goals, the methodology needed to analyse the issue, or the question that needs to be asked. These pre-scientific concerns affect the outcomes of scientific investigation.

Beyond the false narrative of scientific objectivity, is the myth of scientific unity. Feyerabend showed that at no point was there ever a complete scientific consensus on a topic, and that there are no settled questions. The very notion of settling a question goes against the grain of a progressive science, where everything should be challenged, and competing hypotheses proposed. The notion of scientific unity damages the pursuit of knowledge by resisting the paradigm-shifts that are fundamental to new discovery and progress. In practical terms today, we see increasing dogmatism about the “scientific” understanding of fields, from economics to climate science to evolutionary psychology, as if there were hegemonic fields in which participants did not dissent. Such a poor understanding and communication of scientific claims can easily close off the majority from participation in the democratic decisions of the day. Such a view of the world would deprive those who did not operate within narrow bounds of theoretical knowledge from having decision-making autonomy.

Feyerabend feared these social developments and proposed “the separation of state and Church must be complemented by the separation of state and science, that most recent, most aggressive, and most dogmatic religious institution”, believing that scientific progress is a form of human creativity. While it may be a liberating force guiding by our desire to innovate and serve the needs of people, a highly restricted form of scientific investigation that limits scientists to a particular method would have prevented the greatest discoveries in history from coming about. What is needed then is a renewal of the creative spirit in the enterprise of science which would direct it to the goals of people. Science is not some objective understanding of the world, but rather a human enterprise, guided by human desire, and exists only to fulfil the creativity and flourishing of human society.

This anarchism is fundamental to the libertarian vision, for it seeks not one limited vision of control, but a pluralistic conception of knowledge that begins with the embodiment of the individual in the world. What this means in practical terms is that there needs to be a break not only with the perception of a ‘proper way’ to conduct scientific research, but also a break with the belief that science is the sole arbiter of truth and value. Debates in public policy today seek scientific backing, with science-based policy becoming an irrefutable guide to action. While this is heralded as bringing greater accountability and objectivity in decision-making, there can be no such objectivity in a world where disagreement over scientific interpretation will always exist. These are developments that run contrary to the very grain of liberty we value, as they sideline democratic deliberation. This risks descent into a technocratic society devoid of the individual freedom that so characterises the struggle for liberty.

Skepticism and debate are healthy when it comes to political and social debates, so why not when it comes to scientific ones? The closing off of opportunities for social participation based on technical knowledge or agreement with the norm is a view that we ought to oppose, and Paul Feyerabend showed us how.

This piece solely expresses the opinion of the author and not necessarily the organization as a whole. Students For Liberty is committed to facilitating a broad dialogue for liberty, representing a variety of opinions. If you’re a student interested in presenting your perspective on this blog, click here to submit a guest post!

Picture: Wikimedia